Blurred Lines: Segregation at the State Fair of Texas

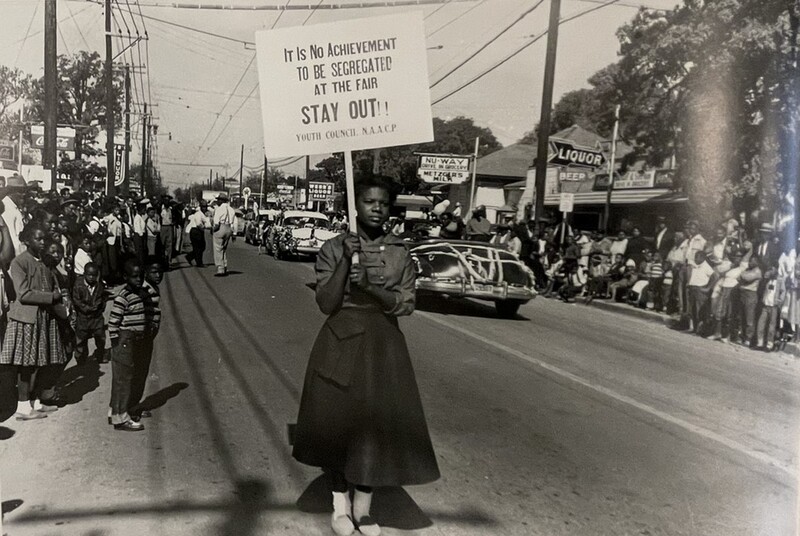

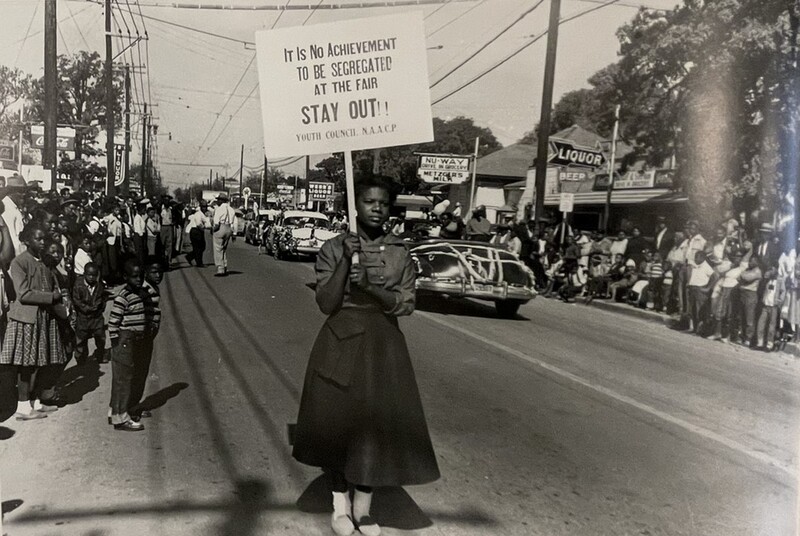

It was a cool morning on October 17, 1955. The 7:00am temperature reported at Dallas Love Field airport registered at a crispy 46.9° Fahrenheit, with NW winds at 3.31mph and no cloud cover.[1] The events occurring later that day signaled the day when thousands of black families would converge upon the State Fair of Texas fairgrounds in Dallas for their annual Negro Achievement Day, a day designated for blacks to attend the segregated fairgrounds. No cloud cover on that date was also the perfect backdrop for all to see the Youth Council of the Dallas Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and their unprecedented plans to challenge those segregated practices.

Led by their Youth Director Juanita Craft, at 7:00am, the young black students prepared to demonstrate and picket against the segregated practices of the beloved fair. (Burrow, 23). Craft was no stranger to the fight for racial equality in Dallas and was known throughout the State of Texas. She experienced racial discrimination before, but perhaps her greatest achievement was leading the youth council that day, in a match which pitted them against the white State Fair officials and some local blacks. (Hazel, 3). Although the segregated policies of Fair Park did not immediately end because of the Youth Council’s protest and demonstration; the blurred lines of desegregation became clearer as the threshold of segregation was challenged. The slow process began to open the State Fair of Texas for all races to enjoy the fun during its annual run.

World’s fairs and state fairs were designed to attract attention to a particular state or town by effective boosterism meant to draw crowds. Some fairs ended with debts, but overall, they were intended to show the modernity and progress of the region where the fairs were held. The current site of the State Fair of Texas in Dallas began in 1886. (Dingus, 2003). There were several fairs within the state during the mid-to-latter part of the nineteenth-century and well into the twentieth-century. The idea and foundation for the first fair in Texas was not located in Houston, TX, nor in Dallas, TX. The concept and later formation of a Texas State Fair debuted in Corpus Christi, TX.

As early as 1851, Colonel Henry L. McKinney, the founder of Corpus Christi, began advertising for a state fair. His notions of a fair began on May 1, 1852, in what he later called the “Lone Star Fair.” Complete with races and a circus, the fair also included an appearance by Don Camerena, the celebrated bullfighter from Mexico. In attendance at the Lone Star Fair that year were Mexicans, Comanche and Lipan Indians, and formerly enslaved blacks. (Warner-Ward, 167-168). Five years after the end of slavery, the city of Houston held a state fair in 1870, but by the end of the decade it no longer existed. (Simek, para 4). Reconstruction was over and many of the freedoms gained by blacks were overshadowed by violence and lynchings. Racial tensions increased near the end of the nineteenth-century after the 1896 U. S. Supreme Court ruling in favor of “separate but equal” laws in Plessy vs. Ferguson.[2]

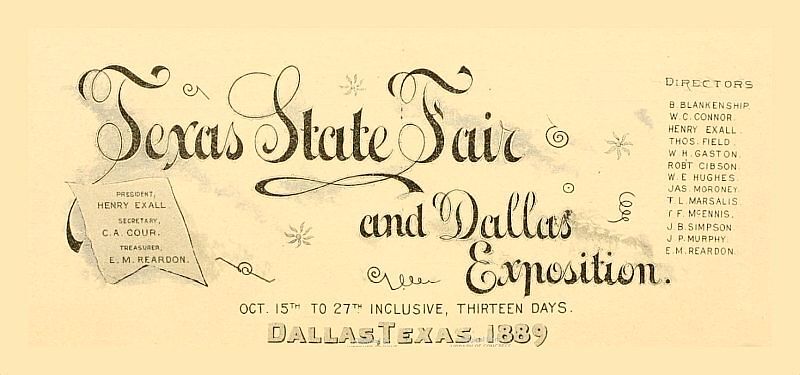

The State Fair of Texas was initially called the Dallas State Fair and Exposition. It began as a private corporation by some Dallas businessmen on January 30, 1886. Factions of the group split to form their own entity called the Texas State Fair and Exposition. By October of that year, the two groups held separate fair events on October 25th and October 26th, respectively. Attendance was estimated at over 100,000 people. The two opposing sides eventually merged in 1887 and officially became the Texas State Fair and Dallas Exposition.[3] Blacks would not attend the fair until their designated Colored People’s Day in 1889.

Designated days were set aside for blacks and other groups. Colored People’s Day and Negro Achievement Day were designed to highlight the gains and achievements of blacks, but the seething reality is that many of the world’s fairs and state fairs, particularly in the United States, were segregated. After the decision to have a segregated Colored People’s Day in 1889, prominent blacks made efforts to secure Booker T. Washington, whose address at the 1895 Atlanta Cotton States Exposition of 1895, sparked much of the racial drama and tension seen in Atlanta. (Perdue, 3). The 1900 Colored People’s Day at the Texas State Fair and Dallas Exposition included Washington, a former slave, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, and a leading black figure of the era.

In 1904, the City of Dallas became the executor of the Texas State Fair and Dallas Exposition and forged a path by which the fair could be more profitable. The arrival of rail lines in 1873 spurred population and economic growth in Dallas and sparked a new period of local promotion and boosterism by Dallas’ business elite. The new period of local boosterism was highlighted by urban development. (Bennett, 32). Promotion of Dallas was the enthusiastic goal of the city’s white businessmen and citizens, but blacks were not involved. By 1910, Colored People’s Day was non-existent. (Burrow, 21). Other groups were also given designated days at the fair.

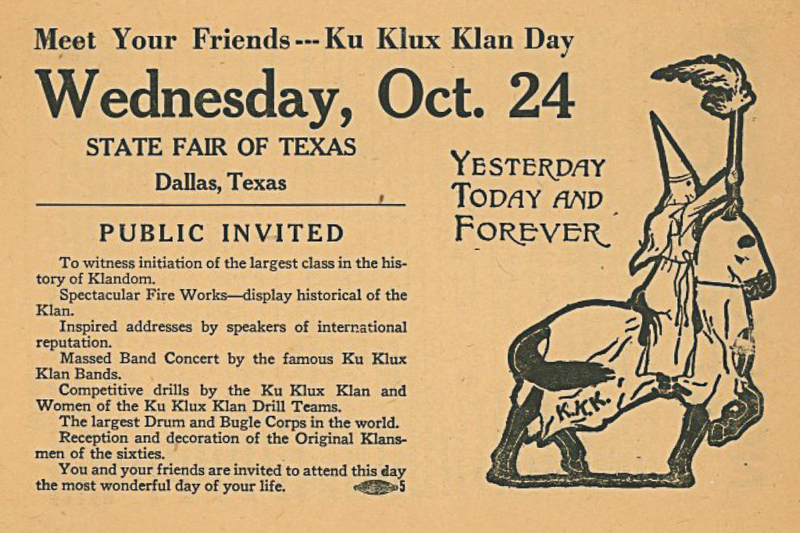

In 1923, there was a Ku Klux Klan Day, which attracted more than 100,000 Klan members and boosted their overall numbers. Blacks would not participate in fair activities again until 1936. (Simek, para. 7). The occasion for black participation in 1936 was to highlight their accomplishments for Negro Achievement Day, which coincided with the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition held in Dallas that year. Despite the continuity of segregation in Texas, Blacks were up for the challenge and sought an opportunity to highlight their achievements.

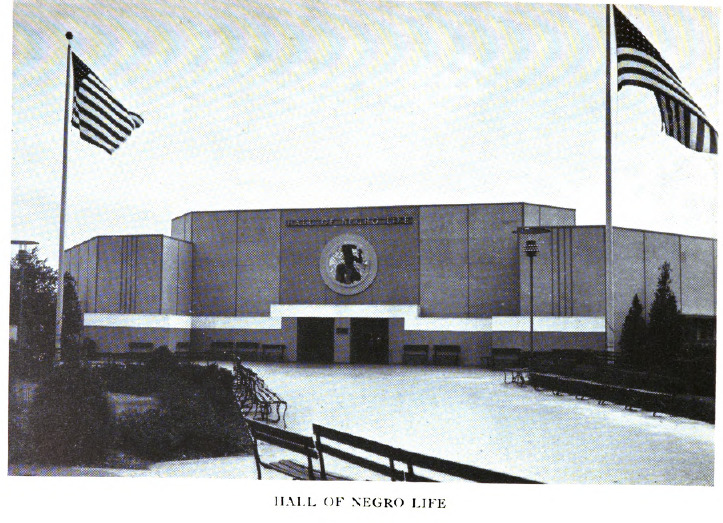

Blacks began to assert themselves in the fight against disenfranchisement and discrimination. Dr. W. E. B. DuBois, a black elite and one of the founders of the NAACP, prepared a ten-page pamphlet for the Centennial. Entitled, What the Negro Has Done for the United States and Texas, DuBois wrote, “… all that is necessary is justice and freedom and understanding between men.”[4] DuBois’s proposed understanding between men was apparent in the planning efforts of the 1936 Centennial. Blacks were allowed to take control of the exhibits to be housed in the Hall of Negro Life building. Jesse O. Thomas, a protégé of Booker T. Washington, served as General Manager of the building. He wrote, “Notwithstanding that there are approximately 900,000 Negroes in the State Of Texas, there are approximately 48,000 in the City of Dallas, neither the State of Texas nor the City of Dallas appropriated a single dime to cover Negro participation in the Texas Centennial.”[5] Blacks had grown accustomed to their needs and wants being ignored. Black participation in Negro Achievement Day at the 1936 Texas Centennial and Exposition opened on June 19, 1936.

Despite attempts by local white newspaper accounts to discredit the attendance and monetary gains of the day, the 1936 Negro Achievement Day and the Hall of Negro Life drew 403,227 visitors. (Thomas, 36). Of those visitors to the Hall of Negro Life building, many of them were white. Lisa Munro, in Investigating World’s Fairs, notes the importance of fairgoers’ perception of their experiences, an area of which scholars know little about. (Munro, 89). Jesse O. Thomas argued that visitation to the building by white citizens was approximately sixty percent. (Thomas, 37). After the Centennial and Exposition ended, the Hall of Negro building was demolished. (Simek, para. 13).

There were no fairs held in Dallas between 1942 – 1945 due to the country’s participation in World War II. The Negro Chamber of Commerce in Dallas worked with State Fair officials and semi-officially ended segregation in 1953, but blacks could not eat at the restaurants and some rides were restricted. (Burrow, 23). By 1957, State Fair officials removed race designations, such as Colored People’s Day, Negro Day, and Negro Achievement Days. On October 12, 1957, the day was labeled as Achievement Day, albeit still segregated. Achievement Day was no longer in use by 1961. Segregation policies and practices at the State Fair of Texas officially ended in Dallas on October 7, 1967. (Burrow, 26).

Desegregation of the fairgrounds allowed people from all races and diverse levels of society to enjoy the food and rides together. The blurred lines of segregation were still blurry, but the threshold had been crossed, at least, as it pertained to the desegregation of the State Fair of Texas in Dallas.

Images