The Lynching of George Hughes

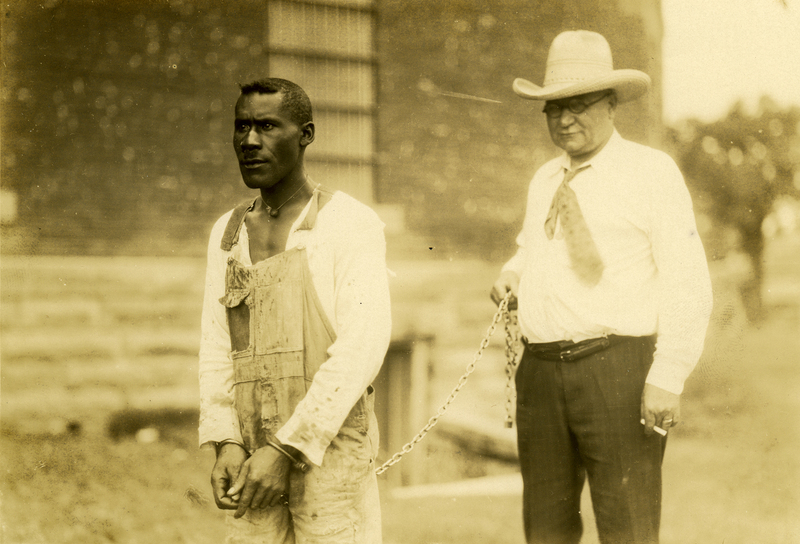

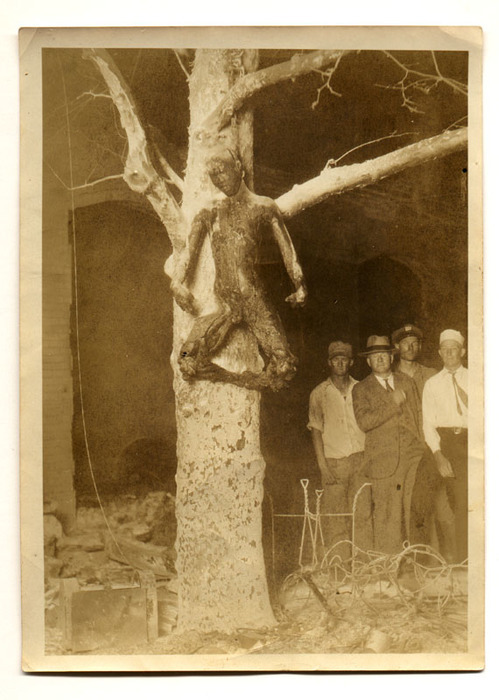

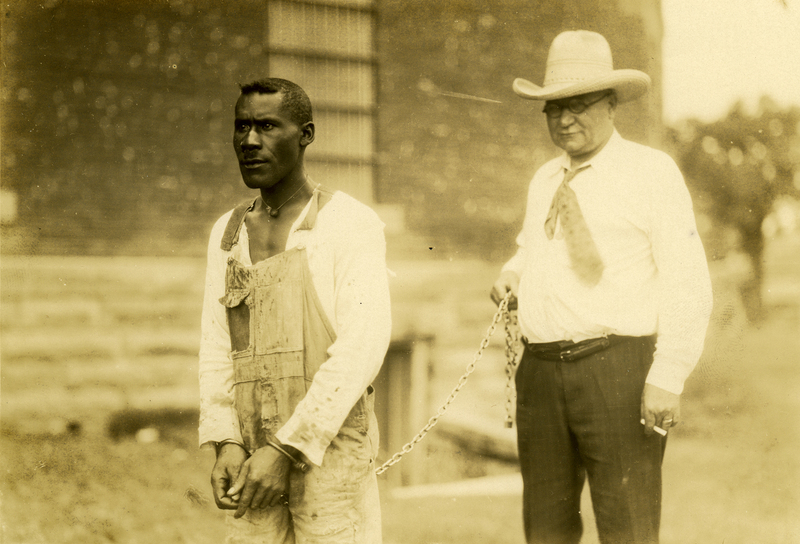

On Friday, May 9, 1930, in Sherman, Texas, the oppressive smell of fresh smoke filled the air. The sound of shattering glass pierced the evening sky. An entire section of the town was up in flames, as was the Grayson County courthouse. The streets were rife with bloodlust and panic. By the end of the night, a man was lynched from a tree, his charred body left dangling from a noose as locals gathered for photographs.

Sherman is the seat of Grayson County, and in some capacity, its identity and its soul have always been in flux. During its early days, Sherman and its surrounding region were populated in large part by transplants from the Upper South, very few of whom were slaveholders. A Unionist sentiment prevailed, and this drew the ire of Confederates. In 1862, between 150 and 200 pro-Union citizens (some from Sherman) were arrested by the state militia, and 42 of them were hanged. Later in the Civil War, Confederate guerrilla William Quantrill and his men spent time in Sherman, and the town would also play host to Jesse James’s honeymoon. Conversely, the postbellum years saw Sherman’s intellectual and academic community expand considerably, with half a dozen colleges and private academies springing up around town; as such, Sherman became known as the “Athens of Texas.” On May 9, 1930, though, Sherman fell far short of these lofty, high-minded attributions, because on this day, the Athens of Texas was a veritable warzone.

What was it that plunged the city into chaos? Never mind that Sherman – and its white farmers – were hit especially hard by the Great Depression, a reality that fueled racial resentment around the country. That certainly played a role. The true catalyst for this madness, however, occurred on Saturday, May 3, when George Hughes, a 41-year-old Black farm worker, was arrested. Hughes had been working for a local farmer, and according to the man’s wife, Hughes arrived at roughly 10:00 AM that morning to collect the $6 owed to him. After the woman told him that her husband was away, Hughes left, only to return armed with a shotgun, at which point he allegedly assaulted the woman. According to the report, Hughes not only fired on pursuers who were alerted to the crime, but also upon the deputy who was summoned to the scene. He promptly surrendered once both barrels of the shotgun were emptied.

Mr. Hughes went on to plead guilty for his alleged crimes, which most assuredly would have ended in the death penalty had his sentence had the opportunity to be carried out. Still, scholars like Monica Martinez, associate professor of history at UT and expert on racial violence in America, argue that Hughes’s guilty plea should – by its very nature – be subjected to intense scrutiny. “It’s a corrupt archive,” she declared in an interview with The Washington Post, noting that such confessions were usually coerced. What’s more, Hughes had no history of violence or trouble with the law. Such was established by author and historian, Arthur F. Raper, in his book, The Tragedy of Lynching. On the contrary, Hughes’s work history was one of high praise. Former employers described him as hardworking and trustworthy, with one noting that Hughes was “the best help about the farm he had ever had.” Adding to the possible invalidity of the guilty plea was Hughes’s apparent (or presumed) intellectual disability. Those who knew him stated that he wasn’t always the brightest, with some referring to him as a half-wit. The question then arises: was George Hughes aware of the ramifications of his guilty plea? Would George Hughes have willingly plead guilty had he known that it would mean his imminent death?

Rumors quickly spread about the nature of the crime. What started as an accusation of rape morphed into stories about Hughes mutilating the woman’s throat and breasts, injuries from which she would surely die. Of course, these were just that: stories. Alas, this sort of sensationalism was par the course for the South. There had long been an inherent abhorrence for interracial relations and miscegenation, with white men feeling compelled to “protect” white women from the sexual “threat” of black men. This deep-seated fear of black men having sex with white women was so prevalent that it played a central role in cinema’s first bona fide blockbuster: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. The first film screened at the White House, it was symptomatic of the deeper racial hysteria that pervaded white society. It was this hysteria – this racially-motivated, hypermasculine tribalism – that facilitated countless lynchings throughout the South, and on May 9, 1930, in Sherman, Texas, it facilitated that and so much more.

Tensions had been mounting throughout the week. That Tuesday, a group of older teens arrived at the jail demanding that Hughes be turned over to them. When the county attorney indicated that Hughes was not there, the boys drenched him with water from a hose, cast rocks through the windows, and uprooted a telephone pole to force an entrance. Governor Dan Moody received a request to dispatch Texas Rangers to stifle any potential violence, and on Thursday, four Rangers – led by Frank Hamer, who headed the posse that killed Bonnie and Clyde – arrived to keep the peace.

As the trial ensued, a crowd numbering some 5,000 gathered outside the courthouse. Frustrations began boiling over when the alleged victim let out a shriek at the sight of Hughes. Spectators rushed the courthouse, with one narrowly missing Hughes. The crowd was held back with tear gas, and the Rangers brandished their guns to keep the increasingly ravenous onlookers at bay. Hughes was promptly evacuated; authorities moved him to the district clerk’s office, a vault of steel and concrete. Two young men doused the courthouse with a gasoline can, and within moments, the storied Grayson County courthouse – first erected in 1876 – was engulfed in a blaze. Try as the fire department might to extinguish the inferno, each and every hose was slashed by members of the raucous mob outside, determined to either root out Hughes or bring the building down on top of him.

As troops from the National Guard started to trickle into town, they were met with a hail of glass bottles, bricks, and boards. The mob attempted to breach the vault to reach Hughes. When tools didn’t work, they resorted to dynamite. When dynamite didn’t work, they took an acetylene torch to the vault and breached the outer layer. With the shell damaged, a dynamite blast was able to punch a hole in the wall.

Inside was Hughes’s lifeless body, smothered to death by the oppressive smoke. The mob was not content to let the dead man lie, however. They pulled him from the burning courthouse, chained him to the back of a car, and dragged him to Sherman’s Black neighborhood. There, they strung up his corpse from a tree across from a Black-owned drug store. Shortly thereafter, the frenzied crowd looted the store and took its furnishings to use as kindling. Stacking it beneath Hughes’s corpse, they ignited the pyre, looking on in satisfaction as his body was scorched by the rising flames. At some point, Hughes’s penis was severed – a testament to the vindictiveness that came with white sexual insecurity. The crowd then turned its attention to the town’s Black population. In a display of unmitigated mob violence, they destroyed Black-owned businesses and ran the Black residents out of town, forcing them to take refuge in thickets, bushes, and sewers.

By morning, Sherman’s Black business district was an ash heap, and George Hughes’s mutilated body – which had been a photo op the night before – was cut down by National Guardsmen. Martial law was declared, and for two weeks, the National Guard guarded the Black district and mounted machine guns around the jail. In the end, only one of the 32 rioters who were arrested was convicted – not for the lynching, but for arson.

Today, there is a push to memorialize the lynching and the subsequent riot. This movement is prompting the expected sort of discourse, with many decrying the proposed memorial as divisive race-baiting, while others are advocating it passionately. In Sherman, the courthouse has been rebuilt. In front of it stands a monument to the Confederacy, erected in 1896 – the first of its kind in Texas to be dedicated at a courthouse. The Black business district is now a parking lot; the dreams and livelihoods of so many – all violently and brutally stolen on that May night in 1930 – paved over with cold, lifeless, passionless concrete. And as for George Hughes? He was buried in a cheap wooden box, laid to rest in an unmarked grave, where he rests to this day.

Images